It’s been a big year for the clean energy transition.

The energy crisis has both made the transition more urgent and complicated, as inflation and supply chain disruptions are changing the economic equation for new projects. Meanwhile, clean energy target dates are sneaking up, as policy is aligning to (hopefully, eventually) make the transition cheaper and easier.

These complications have inspired new thinking and conversations about the clean transition. As I look back at this year’s clean energy news, I noticed five topics catalyzing new, more nuanced discussions, complicating the conversation in a completely necessary way to address the decarbonization of energy markets.

Increased scrutiny of corporate climate targets versus action

We’ve been living through a wild-west era of corporate climate claims with unchecked greenwashing and questionable impact metrics.

That’s bad news, as emissions are impervious to PR spin and careful comms framing. Despite the run on climate commitments, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a report showing energy-related carbon dioxide emissions rose by 6 percent in 2021, to 36.3 billion tons — their highest level, more than offsetting the 2020 dip.

This year there has been a rise in frameworks to understand what climate goals mean — and if corporations are on track to meet them.

As You Sow, a shareholder advocacy organization, launched its “Road to Zero Emissions” report, which dug into the data of 55 of the largest U.S. corporations’ climate plans and compared it to their action. The findings: The vast majority of company climate actions are not yet aligned with global climate goals. Major factors include skimming over emissions buried in supply chains, and over-relying on carbon offsets, instead of transforming operations.

A United Nations-sponsored panel took aim at greenwashing, creating a framework called Integrity Matters for what a credible net-zero emissions plan should look like. The outcome is 10 recommendations that could be used as a rubric for how seriously a company is taking its climate pledges and, hopefully, bring more integrity and trust to climate commitments across the board.

Industrial decarbonization goes mainstream

Industrial emissions — the emissions that go into making things — comprise about 38 percent of global emissions. These emissions, buried in consumer-facing companies’ Scope 3 accounting, are becoming a focus of both policymakers and corporations climate action.

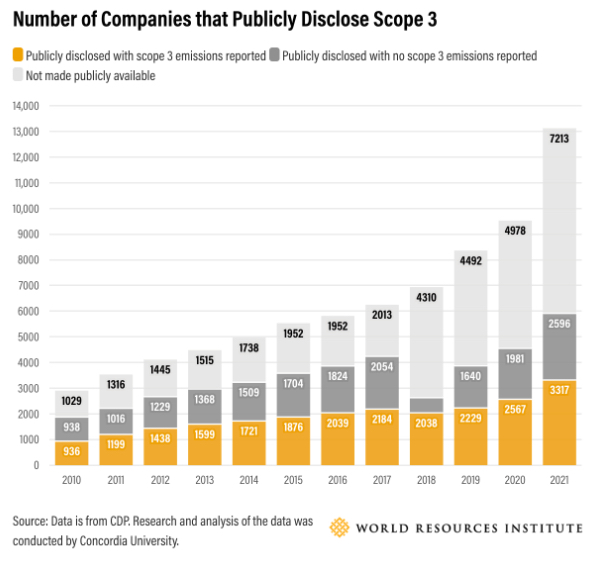

Climate-conscious corporations are increasingly acknowledging their Scope 3 emissions, which accounts for an average of three-quarter of a company’s emissions. Analysis from the CDP and Concordia University shows companies disclosing Scope 3 is up 3.5 fold over the last decade.

Meanwhile, policy is aligning to make it easier for corporations to decarbonize their industrial emissions. Earlier this year, the White House issued its long-awaited guidelines for its Federal Buy Clean Initiative with the aim of spurring the development of low-carbon construction materials. The program outlines buying principles for materials the federal government procures directly or in projects funded by federal dollars.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Energy challenged the research and development community to reduce cost, energy use and emissions associated with heavy industry heating, which includes things such as smelting iron or firing cement in a kiln.

This comes at a time when much is happening in the renewable thermal space. Companies such as Rondo, Brenmiller and Polar Night Energy are exploring novel thermal storage solutions, and technological innovations in geothermal and nuclear fusion have clean energy nerds all atwitter. This comes as partnerships, such as the Renewable Thermal Collaborative, work to align the industry to scale technologies.

Energy efficiency comes back into vogue

Energy efficiency, the most underrated clean energy resource, is having a moment. The reason: the energy crisis suddenly makes the opportunity to save energy more appealing.

The fact that energy efficiency isn’t the first step to every net zero strategy is a head scratcher. But with corporations facing increased energy costs, 71 percent of consumers are more interested in reducing consumption compared to one year ago, according to EY’s Energy Consumer Survey 2022.

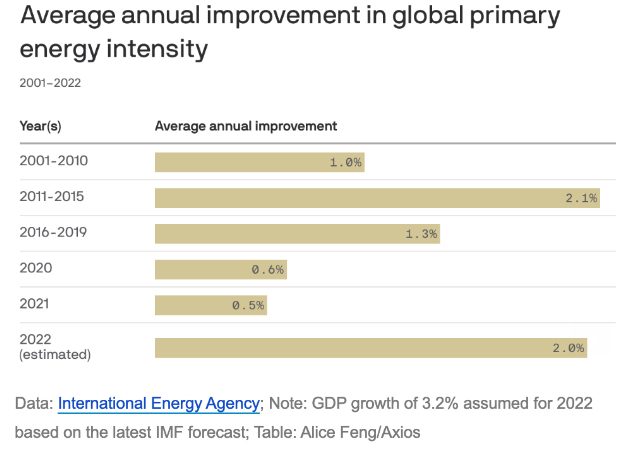

According to the IEA, the world is on track to improve its energy intensity (the energy used relative to economic output) by 2 percent in 2022, after years of weaker improvements.

While trending in the right direction, these improvements are still too modest. To reach net zero emissions by 2050, we’d need 4 percent annual improvements in energy intensity, according to IEA planning scenarios.

Transmission and distribution comes into focus

While the clean energy community has been excited about the proliferation of cheap, clean options, this year seems to be the time when organizations have started to acknowledge the shortcomings of the grid infrastructure to reach our decarbonization goals energy markets.

Earlier this year, a study from Berkeley Lab showed that there is enough renewable energy in the pipeline to bring the U.S. electricity grid to 80 percent carbon free power by 2030. But, thanks to interconnection delays, less than a quarter will likely be built.

With the new tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act, demand for new projects is set to surge.

As a result, policy is beginning to take shape to encourage updates, including $13 billion to modernize and expand the power grid, funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Updating the grid will certainly be an uphill battle, with decades of deferred maintenance needing to be addressed and a patchwork of regulations making updates difficult.

Aligning incentives with outcomes

As the clean energy transition matures, organizations are increasingly working to ensure incentives are aligned with the outcomes we want to achieve.

Meta, for example, is exploring a new financial structure to explore how to send price signals to encourage decarbonization — not just deployment of clean technologies. The tech giant selected three of its Texas energy storage projects, with a combined capacity of 9.9 megawatts (MW), for which it will compensate the project developer based on the emission reductions they create.

A new coalition, Emissions First, is embracing a new accounting framework that moves beyond looking at clean energy generation to focusing on the emission reductions impact of new clean energy projects. Its signatures include Amazon, General Motors and Salesforce.

These initiatives, along with others, are helping to ensure efforts are as impactful as possible.