In many organizations, once the work has been done to integrate a

new system into the mainframe, say, it becomes much

easier to interact with that system via the mainframe rather than

repeat the integration each time. For many legacy systems with a

monolithic architecture this made sense, integrating the

same system into the same monolith multiple times would have been

wasteful and likely confusing. Over time other systems begin to reach

into the legacy system to fetch this data, with the originating

integrated system often “forgotten”.

Usually this leads to a legacy system becoming the single point

of integration for multiple systems, and hence also becoming a key

upstream data source for any business processes needing that data.

Repeat this approach a few times and add in the tight coupling to

legacy data representations we often see,

for example as in Invasive Critical Aggregator, then this can create

a significant challenge for legacy displacement.

By tracing sources of data and integration points back “beyond” the

legacy estate we can often “revert to source” for our legacy displacement

efforts. This can allow us to reduce dependencies on legacy

early on as well as providing an opportunity to improve the quality and

timeliness of data as we can bring more modern integration techniques

into play.

It is also worth noting that it is increasingly vital to understand the true sources

of data for business and legal reasons such as GDPR. For many organizations with

an extensive legacy estate it is only when a failure or issue arises that

the true source of data becomes clearer.

How It Works

As part of any legacy displacement effort we need to trace the originating

sources and sinks for key data flows. Depending on how we choose to slice

up the overall problem we may not need to do this for all systems and

data at once; although for getting a sense of the overall scale of the work

to be done it is very useful to understand the main

flows.

Our aim is to produce some type of data flow map. The actual format used

is less important,

rather the key being that this discovery doesn’t just

stop at the legacy systems but digs deeper to see the underlying integration points.

We see many

architecture diagrams while working with our clients and it is surprising

how often they seem to ignore what lies behind the legacy.

There are several techniques for tracing data through systems. Broadly

we can see these as tracing the path upstream or downstream. While there is

often data flowing both to and from the underlying source systems we

find organizations tend to think in terms only of data sources. Perhaps

when viewed through the lenses of the legacy systems this

is the most visible part of any integration? It is not uncommon to

find the flow of data from legacy back into source systems is the

most poorly understood and least documented part of any integration.

For upstream we often start with the business processes and then attempt

to trace the flow of data into, and then back through, legacy.

This can be challenging, especially in older systems, with many different

combinations of integration technologies. One useful technique is to use

is CRC cards with the goal of creating

a dataflow diagram alongside sequence diagrams for key business

process steps. Whichever technique we use it is vital to get the right

people involved, ideally those who originally worked on the legacy systems

but more commonly those who now support them. If these people aren’t

available and the knowledge of how things work has been lost then starting

at source and working downstream might be more suitable.

Tracing integration downstream can also be extremely useful and in our

experience is often neglected, partly because if

Feature Parity is in play the focus tends to be only

on existing business processes. When tracing downstream we begin with an

underlying integration point and then try to trace through to the

key business capabilities and processes it supports.

Not unlike a geologist introducing dye at a possible source for a

river and then seeing which streams and tributaries the dye eventually appears in

downstream.

This approach is especially useful where knowledge about the legacy integration

and corresponding systems is in short supply and is especially useful when we are

creating a new component or business process.

When tracing downstream we might discover where this data

comes into play without first knowing the exact path it

takes, here you will likely want to compare it against the original source

data to verify if things have been altered along the way.

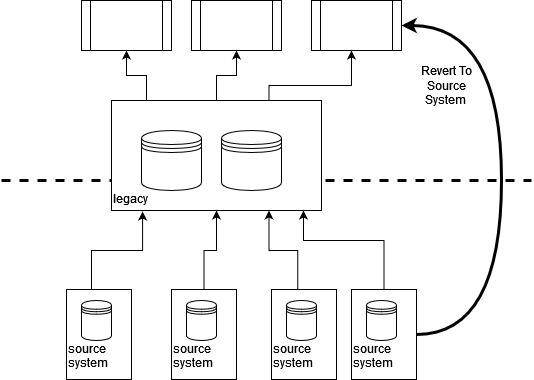

Once we understand the flow of data we can then see if it is possible

to intercept or create a copy of the data at source, which can then flow to

our new solution. Thus instead of integrating to legacy we create some new

integration to allow our new components to Revert to Source.

We do need to make sure we account for both upstream and downstream flows,

but these don’t have to be implemented together as we see in the example

below.

If a new integration isn’t possible we can use Event Interception

or similar to create a copy of the data flow and route that to our new component,

we want to do that as far upstream as possible to reduce any

dependency on existing legacy behaviors.

When to Use It

Revert to Source is most useful where we are extracting a specific business

capability or process that relies on data that is ultimately

sourced from an integration point “hiding behind” a legacy system. It

works best where the data broadly passes through legacy unchanged, where

there is little processing or enrichment happening before consumption.

While this may sound unlikely in practice we find many cases where legacy is

just acting as a integration hub. The main changes we see happening to

data in these situations are loss of data, and a reduction in timeliness of data.

Loss of data, since fields and elements are usually being filtered out

simply because there was no way to represent them in the legacy system, or

because it was too costly and risky to make the changes needed.

Reduction in timeliness since many legacy systems use batch jobs for data import, and

as discussed in Critical Aggregator the “safe data

update period” is often pre-defined and near impossible to change.

We can combine Revert to Source with Parallel Running and Reconciliation

in order to validate that there isn’t some additional change happening to the

data within legacy. This is a sound approach to use in general but

is especially useful where data flows via different paths to different

end points, but must ultimately produce the same results.

There can also be a powerful business case to be made

for using Revert to Source as richer and more timely data is often

available.

It is common for source systems to have been upgraded or

changed several times with these changes effectively remaining hidden

behind legacy.

We’ve seen multiple examples where improvements to the data

was actually the core justification for these upgrades, but the benefits

were never fully realized since the more frequent and richer updates could

not be made available through the legacy path.

We can also use this pattern where there is a two way flow of data with

an underlying integration point, although here more care is needed.

Any updates ultimately heading to the source system must first

flow through the legacy systems, here they may trigger or update

other processes. Luckily it is quite possible to split the upstream and

downstream flows. So, for example, changes flowing back to a source system

could continue to flow via legacy, while updates we can take direct from

source.

It is important to be mindful of any cross functional requirements and constraints

that might exist in the source system, we don’t want to overload that system

or find out it is not relaiable or available enough to directly provide

the required data.

Retail Store Example

For one retail client we were able to use Revert to Source to both

extract a new component and improve existing business capabilities.

The client had an extensive estate of shops and a more recently created

web site for online shopping. Initially the new website sourced all of

it’s stock information from the legacy system, in turn this data

came from a warehouse inventory tracking system and the shops themselves.

These integrations were accomplished via overnight batch jobs. For

the warehouse this worked fine as stock only left the warehouse once

per day, so the business could be sure that the batch update received each

morning would remain valid for approximately 18 hours. For the shops

this created a problem since stock could obviously leave the shops at

any point throughout the working day.

Given this constraint the website only made available stock for sale that

was in the warehouse.

The analytics from the site combined with the shop stock

data received the following day made clear sales were being

lost as a result: required stock had been available in a store all day,

but the batch nature of the legacy integration made this impossible to

take advantage of.

In this case a new inventory component was created, initially for use only

by the website, but with the goal of becoming the new system of record

for the organization as a whole. This component integrated directly

with the in-store till systems which were perfectly capable of providing

near real-time updates as and when sales took place. In fact the business

had invested in a highly reliable network linking their stores in order

to support electronic payments, a network that had plenty of spare capacity.

Warehouse stock levels were initially pulled from the legacy systems with

longer term goal of also reverting this to source at a later stage.

The end result was a website that could safely offer in-store stock

for both in-store reservation and for sale online, alongside a new inventory

component offering richer and more timely data on stock movements.

By reverting to source for the new inventory component the organization

also realized they could get access to much more timely sales data,

which at that time was also only updated into legacy via a batch process.

Reference data such as product lines and prices continued to flow

to the in-store systems via the mainframe, perfectly acceptable given

this changed only infrequently.